On May 22, 1971 – 50 years ago this Saturday – a high-powered audience of politicians, religious leaders, educators and even Hollywood stars, gathered for the dedication of the LBJ Presidential Library in Austin. Then-President Richard Nixon led the honors for his predecessor’s project.

Lyndon Baines Johnson’s would be the first presidential library located in Texas – the George W. Bush and George H.W. Bush libraries are in Dallas and College Station. The LBJ Library commemorate one of the most turbulent, consequential presidencies of the 20th century, and, in the mold of its namesake, it was the first really big, grand facility of its kind to be built.

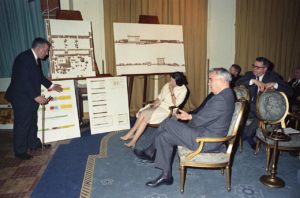

President and Mrs. Johnson stand, along with other dignitaries, at the dedication of the LBJ Library in May, 1971.

Michael Rusnak, LBJ Presidential Library

The 1971 dedication took place on an outdoor platform, just south of the new library.

“President Nixon was there. President Johnson’s cabinet was there. Gov. John Connally was there. Dr. Billy Graham was there,” said Ben Barnes, who was Texas’ lieutenant governor at the time He’s now vice chair of the LBJ Foundation.

Nixon spoke first, accepting the new library on behalf of the American people – presidential libraries are built with private funds, but operated by the National Archives, Johnson rose to acknowledge his achievement – a massive ten story structure that then held 31 million pages of archives – it’s up to 45 million pages, today, including papers given by Johnson associates and members of his government.

As the dignitaries celebrated the library, some 2.000 protesters – according to the New York Times – chanted and banged trash can lids, kept several blocks away by police. The Vietnam War, which escalated dramatically during Johnson’s time in office, was still raging, and in May 1971, many were in no mood to join the in celebrating LBJ’s legacy.

But on the grounds of the new LBJ Library, a cross-section of American political leaders paid tribute, including Barry Goldwater – the man Johnson had defeated in 1964.

On the platform, Johnson cut a striking figure.

“We all had on dark suits. But President Johnson, and I always remember, wore a tan cotton suit. But he does stand out on the platform because he was the only person in that light colored suit,” Barnes said.

Johnson’s remarks at the dedication were brief. He offered a vision for the ways in which the library would educate and inform future generations. And he made a commitment to openness and transparency. “History, with the bark off,” he called it, as the sounds of protest remained audible in the distance.

“There is no record of a mistake, or an unpleasantness, or a criticism that is not included in the files here,” Johnson said. “We have papers from 40, some very turbulent, years of public service, and we put them all here in one place, for friends and foes to judge.”

Indeed, the library has provided some of the most remarkable historical artifacts of any presidency – hours of recordings Johnson made of his Oval Office telephone conversations. The tapes feature Johnson cajoling, bullying and sharing confidences with everyone from uncooperative senators to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

In August 1965, King warned Johnson in a phone call that police violence and hopelessness among Black Americans could spark a “full scale race war” following the bloody Watts riots in Los Angeles. During the call, Johnson emphasized the need to fight poverty, and the political challenges he faced trying to do it.

“We’ve got to have some of these housing programs, and we’ve got to get rid of some of these ghettos, and we’ve got to get these children out of where the rats eat on them at night, and we’ve got to get em some jobs,” he said.

LBJ, who died in 1973, had hoped his White House recordings would not be made public for 50 years. But once their existence became known, the library began releasing them, parceling them out over a fifteen year period.

“In the early 1990s, Mrs. Johnson, who was still very vigorous and very much part of daily life at the LBJ Library, made a decision, along with the administration of the library at that time to go ahead and start processing and releasing the LBJ phone recordings, so they wound up being released well ahead of the schedule that LBJ himself had imagined,” Said Mark Lawrence, who has been the director of the LBJ Library since January 2020.

Recently, audio diaries made by Lady Bird Johnson have added to what we know about the first lady’s role in LBJ’s life and work. The diaries are now the source for a new biography and podcast that also illuminate her role as a witness to history, including the day in Dallas when President John F- Kennedy was assassinated.

“Friday, November 22nd. It all began so beautifully. The streets were lined with people. Lots and lots of children, all smiling, placards, confetti, people waving from windows. Suddenly, there was a sharp, loud shot,” Lady Bird Johnson said in her audio diary.

The tapes also show that Lady Bird Johnson played a major role in the creation of the library.

“Mrs. Johnson was undoubtedly really important,” said library director Mark Lawrence. “She, after all, was the UT alum. And she played a really important role in the design, in creating the festivities, of course, around the opening of the library. And then she would go on to be such a central fixture to the library and its programs for many, many years thereafter until she passed away in 2007.”

Lady Bird Johnson visited other libraries and sites and took on the early planning stages. She hosted numerous meetings at the White House to discuss the designs with Gordon Bunshaft until the final design was complete. May 12, 1966,

Unknown, LBJ Presidential Library

It was Lady Bird Johnson who identified a building whose architectural style she thought would be a match for her husband’s vision. She was inspired by Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

The Beinecke’s architect, Gordon Bunshaft, was hired to design the LBJ library. Once the University of Texas made clear that it wanted the building on its campus, the pieces began to fall into place. After LBJ’s term ended in 1969, the Johnsons took an increasingly active role.

“There are many wonderful pictures of President Johnson and Mrs. Johnson on the grounds, looking at the building as it’s under construction. They had their picture taken at just about every angle of the building,” Lawrence said.

The library sits near the northeast corner of UT’s Austin campus. The land is also home to the LBJ School of Public Affairs, which opened a year before the library and the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History. But the library dominates. Lawrence says Johnson wanted something big all along.

“I think he wanted to convey grandeur – the importance of the presidency, the importance of the presidency, and his own contributions to American life,” he said.

And the institution’s first purpose, housing the physical records of the Johnson presidency, was visually apparent to visitors in 1971, as it is today. Row upon row of red archive boxes stored on the upper floors – their presidential seals facing forward – are visible from the ground level.

Lady Bird Johnson got the idea to put the archives front and center when she visited the Harry Truman Presidential Library and found his papers were less prominent.

Spencer Selvidge / KUT News

“Some more dramatic use ought to be made of them – those papers,” she recorded in her audio diary. “They could still be secure, behind glass partitions. Some use could be made of color. There could be some displays, highlight the outstanding achievements of a president’s year.”

Over the past five decades, millions of visitors have passed through the library’s permanent museum exhibits, which chronicle civil rights, voting rights, Johnson’s anti-poverty programs and the Vietnam War.

“We try our best to capture the sources of LBJ’s big ideas, the sources of his effectiveness as a politician that grows out of his early career,” Lawrence said. “And then, of course, the heavy emphasis is on the presidency itself. And then another important mission for the museum is to convey the lasting impact – the legacies of the Johnson presidency.”

The library has also played host to an array of public programs, speakers and special events over the years, including a 2014 civil rights summit, with President Barack Obama in attendance.

“I would say that the LBJ Library was really the first to attach a high priority to this kind of programming, to the goal of being an active voice in public debate, going well beyond the period of the presidency itself,” Lawrence said.

The animatronic LBJ replica tells stories to museum visitors.

Spencer Selvidge / KUT News

LBJ’s outsized personality is part of the museum, too – from his Central Texas boyhood, to an almost life-sized replica of Johnson’s Oval Office that features original furnishings, along with the three televisions he used to keep a constant eye on what network news anchors were saying about him. There’s even an animatronic version of the 36th president – a replica that moves and speaks. Passersby hear LBJ tell a series of homespun “after dinner” stories.

On its 50th anniversary, the LBJ Library remains closed to the public, as pandemic precautions continue. Library director Lawrence says the building will reopen gradually, beginning this summer.

For now, visitors can view a new web site featuring the “greatest hits” as Lawrence says, of the Johnson phone recordings, along with the documents and photos the contextualize the tapes.